Chemical and Physical Causes of Coin Toning (Silver and Other Metals)

Coins from the pre-1964 era (e.g. 1950s–early 1960s) often develop toning, which is a thin tarnish or patina on the metal surface caused by slow chemical reactions with the environment (What is Coin Toning? How Does It Affect Coins and Their Value? | CoinNews). For silver coins (90% silver alloy in dimes, quarters, half dollars through 1964), the primary reaction is with trace sulfur-containing gases in air, forming silver sulfide (Ag₂S) on the surface (What causes coins to tone – ICCS) (All About Toned Morgans | Monster Toned Morgans). This silver-sulfide film is usually extremely thin and transparent, producing iridescent colors through thin-film interference – different thicknesses of tarnish film reflect light in different colors, yielding the rainbow hues prized by collectors (What causes coins to tone – ICCS) (All About Toned Morgans | Monster Toned Morgans). Over time, as the film thickens, the tone progresses from light golden to blues and eventually dark grey or black when very thick (fully tarnished) (What causes coins to tone – ICCS). Copper, used in cents (95% copper) and as the remainder in silver coins (10% copper), tarnishes by a similar process but with different chemistry. Copper reacts readily with oxygen and sulfur compounds to form oxides and sulfides, often at even faster rates than silver under similar conditions (What causes coins to tone – ICCS). However, because copper’s oxides are less reflective, toned copper usually shows duller hues (reddish-brown, violet, or green patina) arising from compounds like cuprous oxide (red), cupric oxide (brown/black), or basic copper sulfates/chlorides (green) rather than vibrant rainbow films (What causes coins to tone – ICCS) (What causes coins to tone – ICCS). Nickel, which in this era was present in the 5-cent coin (25% Ni, 75% Cu), is comparatively inert – pure nickel forms only an extremely thin, nearly invisible oxide layer (What causes coins to tone – ICCS). Thus, silver-copper alloys tend to tone most visibly, while coins with higher nickel content (nickels) or gold (proof coins had no gold then, but generally gold is very non-reactive) tone much less or only subtly over long periods (What causes coins to tone – ICCS).

In summary, pre-1964 U.S. coin surfaces tone because their metals gradually oxidize or react with sulfur compounds in the air. Silver sulfide on silver coins is the main culprit behind the dramatic “rainbow” toning seen on 90% silver pieces (All About Toned Morgans | Monster Toned Morgans). Copper-rich coins form oxides/sulfides that manifest as brown, red, or green tarnish (the familiar patina on old pennies) (What causes coins to tone – ICCS) (What causes coins to tone – ICCS). This tarnishing is a natural, slow corrosion process and, if uniform and light, does not typically damage the coin’s metal – it is often even considered attractive by numismatists when it forms an even, multi-color toning pattern (The Evolution of Proof-Set Packaging – Los Angeles Times). However, heavy or uneven toning can become unsightly or, in extreme cases, corrosive if compounds like copper sulfates or chlorides form. The key triggers for these reactions lie in the coin’s storage environment and packaging, as discussed next.

Role of 1950s–60s Mint Cellophane Packaging in the Toning Process

Many collectors have observed that U.S. Mint coins from the 1950s and early 1960s often tone while still sealed in their original “Mint Set” or “Proof Set” cellophane wrappers. The reason is that the packaging materials used by the Mint at that time were not inert – in fact, they frequently contributed to the very chemical reactions that cause toning (Early Proof Set Packaging Damaged Coins – Numismatic News) (Early Proof Set Packaging Damaged Coins – Numismatic News). Early proof sets (1950–mid-1955) were packaged in soft cellophane sleeves that were stapled together and placed in small cardboard boxes (Early Proof Set Packaging Damaged Coins – Numismatic News) (The Evolution of Proof-Set Packaging – Los Angeles Times). Unfortunately, the cardboard and paper materials had high sulfur content and acidity. Over years, sulfur from the packaging migrated onto the coins and reacted with the silver surfaces, inducing tarnish (Early Proof Set Packaging Damaged Coins – Numismatic News). It was common to see coins developing discoloration around the staple areas or wherever the cellophane or tissue paper contacted them. Contemporary reports note that these “foggy” cellophane envelopes “weren’t inert, … tarnishing their surfaces” and even imparting a haze that could be difficult to remove (Early Proof Set Packaging Damaged Coins – Numismatic News). In essence, the coins were sealed along with reactive chemicals that accelerated toning.

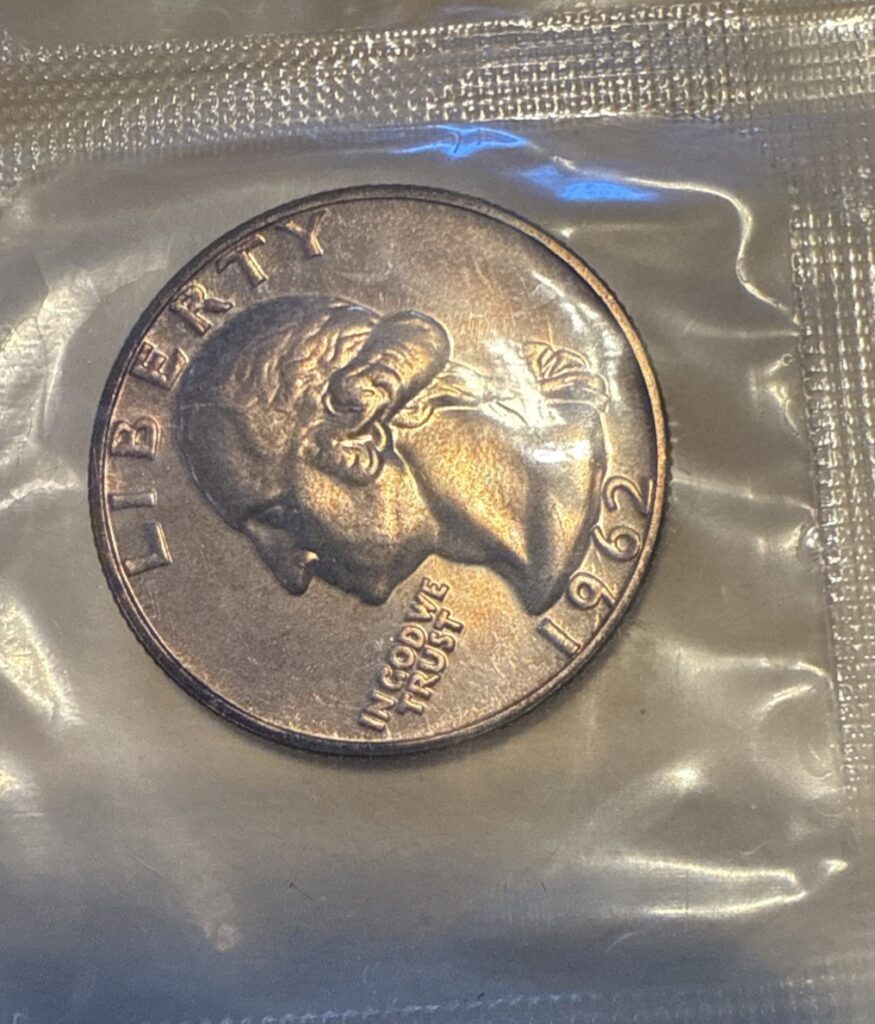

In mid-1955 the U.S. Mint responded to these issues by changing proof set packaging to a new “flat pack” style: coins were sealed in compartments of a folded polyethylene or cellophane sheet (often simply called cello), and no staples or sulfur-laced boxes were used (The Evolution of Proof-Set Packaging – Los Angeles Times). Likewise, starting in 1959 the Mint Sets (uncirculated coin sets) switched from paper boards to clear cellophane sleeves with individual pockets for each coin (Image Gallery | Packaging Styles for Mint Sets). These changes eliminated the obvious sulfur-laden cardboard, but the new plastic “cello” was still not chemically inert. Mint cellophane of that era is now known to be porous and even slightly hygroscopic, meaning it allows air and moisture to pass through and can even retain water vapor (Preservation and Safekeeping of Coins). Any pollutants or sulfur compounds in the air can permeate the plastic and reach the coin. Moreover, the cellophane itself often contained trace chemicals from its manufacturing (the cellophane production process and any plasticizers or additives) – notably, trace sulfur or acidic volatiles that could outgas over time (storing silver in zip lock plastic bags – www.925-1000.com) (Preservation and Safekeeping of Coins). A conservation guide notes that cellophane can attack silver by leaching sulfur compounds, forming silver sulfide and darkening the coin’s surface (Preservation and Safekeeping of Coins). In effect, even though the Mint’s clear flat packs protected coins from fingerprints and handling, they did not create an inert, sealed microclimate. Instead, the coins remained susceptible to slow chemical reactions inside the wrapper. Many coin experts therefore caution against long-term storage in original Mint cellophane: as one notes, “the material was not inert, so unwanted toning, tarnish, corrosion, etc. can occur” in these packs (Storing Coins in the Mint Cello for Long Time Storage ? | Coin Talk). Over decades, it is common to see original Mint-sealed coins develop a film of toning – sometimes beautifully rainbow-colored, other times patchy, gray, or spotty if the reaction was uneven (What you need to know about mint packaging – NGC Chat Boards). The cellophane’s tendency to trap moisture and impurities near the coin can even lead to milky spots or haze on proofs, or slight corrosion on less-resistant metals, if stored in poor conditions (Storing Coins in the Mint Cello for Long Time Storage ? | Coin Talk) (Preservation and Safekeeping of Coins). In summary, the mid-century Mint packaging contributed to toning by providing both a source of reactive vapors (sulfur, acids) and a semipermeable enclosure that let atmospheric gases interact with the coin’s metal.

It’s worth noting that not all toning from original packaging is considered bad. Collectors sometimes value coins with “original toning” from Mint sets, as it can be a hallmark of originality and, if aesthetically pleasing (for example, an even amber, blue, or multicolor tone), may add a premium (Image Gallery | Packaging Styles for Mint Sets). The Mint’s choice of cellophane packaging inadvertently produced countless naturally toned coins. In some cases, the reaction was gentle enough to yield attractive iridescent toning without pitting the surface. In other cases – especially where the cellophane seal was imperfect or the sulfur content high – coins toned heavily or unevenly (for instance, a half dollar might show a crescent of color where it was nearest the edge of the envelope, and remain untoned on the other side). The key takeaway is that the original plastic mint wrappers were not neutral storage containers: they actively influenced the coins’ surfaces over time through chemical interaction.

Environmental Factors (Humidity, Temperature, Air Quality, Light) Affecting Toning in Cello Packs

Beyond the composition of the wrapper itself, the storage environment of the cello-sealed coins plays a major role in the rate and extent of toning. The chemical reactions that cause toning (oxidation, sulfide formation) are all accelerated by heat and moisture. If a Mint Set was stored in a hot, damp attic, the coins will tone much faster (and likely darker) than those stored in a cool, dry safe. In fact, studies note that the speed of tarnish film buildup is a function of several factors: temperature, relative humidity, air composition, and time (What causes coins to tone – ICCS). Warm and humid conditions provide more energy and a better medium for chemical reactions, causing sulfide/oxide layers to form more quickly. One numismatic source explains that “moderate, dry climates are unlikely to produce as thick a film as hot, humid climates might over the same time frame.” Likewise, coins stored in polluted or sulfur-rich atmospheres (e.g. in industrial cities or near freshly varnished wood, rubber, or high-sulfur paper) will tone faster than those in clean air (What causes coins to tone – ICCS). For example, a sealed coin in an environment with coal heating or automotive exhaust (both emit sulfur compounds) might develop a dark tone in a decade, whereas the same coin in an air-conditioned, filtered environment might stay bright for much longer.

The mint cellophane packaging, being permeable to air and moisture, means the micro-environment inside the coin sleeve eventually equilibrates with the outside environment (Preservation and Safekeeping of Coins). If the ambient air has high humidity, the cellophane will actually absorb and hold water vapor, maintaining a damp atmosphere around the coin that promotes oxidation (Preservation and Safekeeping of Coins). Similarly, any sulfur dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, or other tarnishing pollutants in the room air will seep into the packet and react with the coin. Thus, environmental control is crucial: A pre-1964 Mint Set kept in a stable, climate-controlled setting can remain untoned or only lightly toned for decades (Storing Coins in the Mint Cello for Long Time Storage ? | Coin Talk), whereas one kept in a basement or attic might tone dramatically. Collectors on forums have noted that many 1960s cello-pack coins that were stored well are still shiny, while others “with some sets that are bad” toned heavily due to less ideal storage (Storing Coins in the Mint Cello for Long Time Storage ? | Coin Talk).

Light exposure is another factor often questioned. Normal visible light has little direct effect on toning, aside from the fact that exposure to sunlight can heat the coins and packaging. Ultraviolet (UV) light might, over extremely long periods, contribute to polymer degradation (making the cellophane release more reactive chemicals) or slight oxidation changes, but in general toning is driven more by chemistry than by light. One expert remarked that “sunlight alone isn’t going to speed up toning except by warming the coin” (Sunlight and toning – US, World, and Ancient Coins – NGC Forums). However, prolonged light exposure can sometimes fade certain patinas or cause uneven toning if parts of a coin are covered (leading to so-called “target toning”). In the context of original Mint packaging, light might degrade the envelope or plastic over decades, indirectly affecting toning, but humidity and air pollutants are far more influential.

To minimize toning, numismatic preservation experts recommend storing coins in a cool, dry environment with stable temperatures, away from materials that off-gas sulfur or acids (Caring for your coins – Bank of Canada Museum). The Bank of Canada’s conservation guidance, for instance, warns that common materials like wool, felt, oak, and rubber can emit “nasty acidic gases” that tarnish coins, and emphasizes that proper storage (ideally in inert holders with desiccants or air filters) is key to preservation (Caring for your coins – Bank of Canada Museum) (Caring for your coins – Bank of Canada Museum). In the 1950s and 60s, such modern storage aids were not used for Mint products, so the toning we see today on pre-1964 coins is the cumulative result of their exposure over time. If the original wrappers were stored in an envelope in a desk drawer in arid Phoenix, the coins might still be blast white; if they sat in a humid Mid-Atlantic garage, they likely exhibit golden, blue, or even black toning now. The combination of non-inert packaging and ambient environmental conditions ultimately determines the extent of toning inside original Mint cellophane.

U.S. Mint Packaging Practices (1940s–1960s): Materials and Changes

It is helpful to understand the historical packaging methods for U.S. Mint coin sets in this era, because changes in materials were often driven by the very problems of tarnish and coin protection:

- 1947–1958 Uncirculated “Double Mint Sets”: The Mint sold annual uncirculated sets in this period (except 1950) packaged in cardboard holders. Each coin denomination from each mint (Philadelphia and Denver) was mounted between cardboard panels with printed paper backing, usually two examples of each coin (one showing obverse, one reverse) (United States Mint coin sets – Wikipedia). These cardboard panels were then placed in a manila paper envelope for delivery (Image Gallery | Packaging Styles for Mint Sets). Over time, the acidic paper and sulfur in the cardboard caused many coins to tone or discolor. The acidity of the paper could leach into the coins, yielding anything from deep brown tarnish to vivid “album toning” on silver coins (Image Gallery | Packaging Styles for Mint Sets). Collectors have noted that beautifully rainbow-toned coins often emerged from these early Mint sets (when the toning happened evenly), while others turned dull and dark. This packaging is inherently unstable for long-term preservation, as evidenced by the toning and even occasional corrosion seen on coins that remained in their 1940s–50s Mint sets for decades.

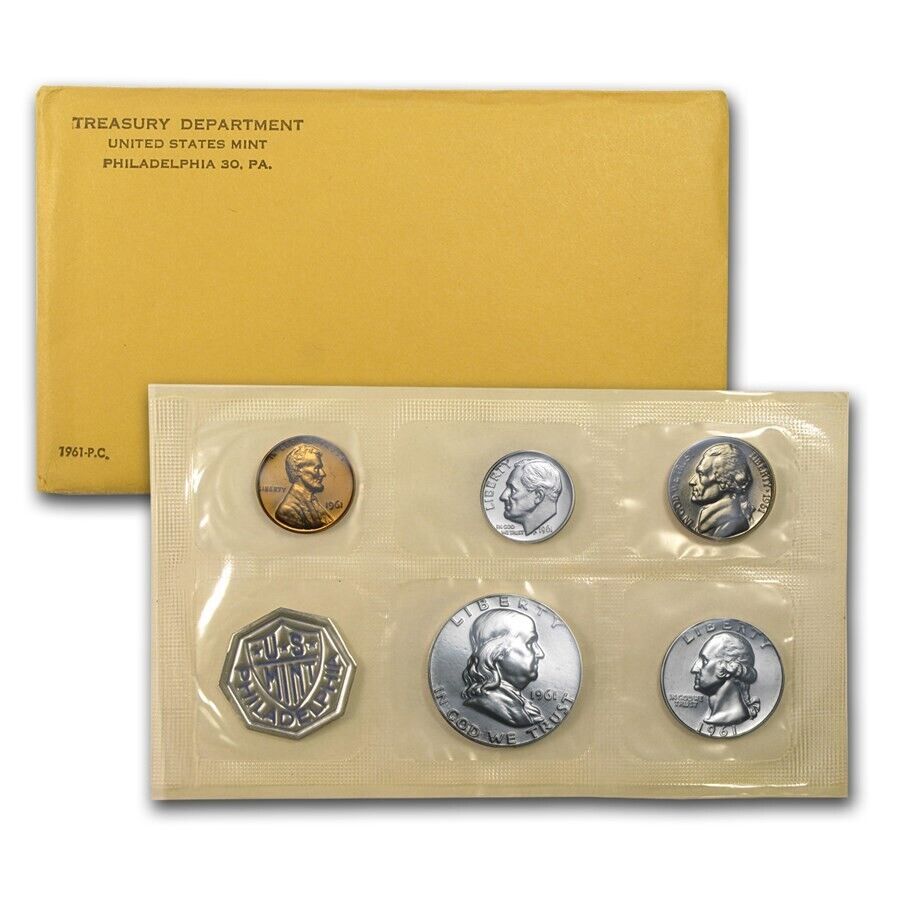

- 1950–1955 Proof Sets (Boxed): When the U.S. Mint resumed Proof coinage in 1950, it packaged proof sets in small cardboard boxes. Inside, each coin was individually sealed in a transparent cellophane envelope, and all envelopes were stapled together and wrapped in tissue (Early Proof Set Packaging Damaged Coins – Numismatic News). While novel at the time, this method introduced multiple tarnish sources: sulfur in the box and tissue paper, steel staples that could rust, and non-airtight cellophane. Indeed, many early 1950s proof coins toned heavily, especially around the staple areas or on sides facing the sulfurous cardboard (Early Proof Set Packaging Damaged Coins – Numismatic News). Some coins even acquired “staple burns” or spots where rust from staples or sulfur caused concentric toning. By 1954–55 the Mint realized the packaging itself was harming the coins’ brilliance (Early Proof Set Packaging Damaged Coins – Numismatic News). Customer complaints and tarnish damage prompted a change.

- 1955 Transition to Flat Pack Proof Sets: Midway through 1955, the Mint introduced a new packaging for proof sets – a “flat pack” heat-sealed plastic sleeve. The coins (cent, nickel, dime, quarter, half) were arranged in a single flat cellophane sheet with individual compartments, then inserted in a manila mailing envelope instead of a box (The Evolution of Proof-Set Packaging – Los Angeles Times). Late 1955 proof sets and all sets 1956 through 1964 were issued in this flat cellophane packaging, tucked inside an orange-ish Treasury envelope. This innovation eliminated staples and greatly reduced the sulfur exposure (the envelopes were less sulfurous than the old boxes). It also allowed both sides of each coin to be visible through the clear film. However, the soft plastic was still chemically reactive to an extent, as discussed earlier. Many 1956–1964 proof coins have developed light golden toning or milky hazes in the areas where the plastic off-gassed or where microscopic gaps let air in. Still, this was considered an improvement – it preserved the mirror-like surfaces better than the 1950–54 method, which often left coins hazy or spotted (Early Proof Set Packaging Damaged Coins – Numismatic News). Collectors generally prefer flat-pack proof sets today because they avoided the staple damage and heavy toning that plagued the boxed sets. By 1965, the Mint stopped issuing proof sets temporarily (instead issuing “Special Mint Sets”), and when proofs resumed in 1968 they came in rigid acrylic holders, marking the end of the cellophane era.

- 1959–1964 Uncirculated Mint Sets (Soft Pack): Following the proof set changes, the Mint also revamped the Uncirculated set packaging in 1959. Instead of the old double sets in cardboard, a new “official Mint Set” was sold containing one of each coin from each mint, sealed in cellophane like the proofs (Image Gallery | Packaging Styles for Mint Sets). The Philadelphia coins were in a sleeve edged with blue, and Denver coins in a sleeve edged with red (these color-coded cellophane strips helped identify the mint). A decorative Mint token was included in each sleeve. The two sleeves (one per mint) were then sandwiched between cardstock and placed in an outer envelope for mailing (Image Gallery | Packaging Styles for Mint Sets). This packaging made for a much more compact and attractive presentation, and it protected coins from direct contact with paper surfaces. Yet, as with the proof packs, the plastic was not airtight or sulfur-free. Over the ensuing decades, many of these 1959–64 uncirculated coins acquired toning – typically starting at the rim or wherever air might seep in. Silver coins in particular often turned a golden-gray, sometimes with rainbow peripheral toning. Copper cents in the Mint cello packs sometimes mellowed from bright red to reddish-brown due to oxidation. Notably, the toning in these official soft-pack Mint Sets is natural and variable: some sets stored well have coins still brilliantly untoned, whereas others (especially those kept in adverse climates) show extensive toning. The Mint Set packaging was an improvement in convenience, but not a long-term archival solution. It wasn’t until much later (starting in the 1970s–80s) that the U.S. Mint adopted near-airtight hard plastic holders for uncirculated sets (United States Mint coin sets – Wikipedia).

Summary of Materials and Changes: In the pre-1964 era, U.S. Mint packaging evolved from reactive paper and cellophane materials toward more inert ones, largely because those early materials caused toning and damage. The mid-1950s saw a shift from high-sulfur paper packaging to less reactive plastic film for both proof and uncirculated sets (The Evolution of Proof-Set Packaging – Los Angeles Times) (Image Gallery | Packaging Styles for Mint Sets). This reduced the worst staining and corrosion (no more sulfur boxes or rusty staples by 1956), but it did not eliminate toning risk. Collectors today treasure many coins from these years specifically because the original packaging produced distinctive toning patterns over time. At the same time, numismatic experts often warn that if preservation (rather than toning) is the goal, coins should eventually be moved to inert holders. By 1965–1967, the Mint experimented with Special Mint Sets (SMS) which featured a different packaging (for example, 1966–67 SMS came in hard plastic cases) to improve coin protection (U.S. Proof Set Facts – What You Need To Know Before Collecting – Portsmouth Coin & Currency Co). Finally, in 1968 the Mint permanently shifted proof sets to hard Lucite-style cases, greatly slowing toning by sealing coins away from air. The legacy of the 1950s–60s cellophane wrappers, however, is still seen in the beautiful (and sometimes not-so-beautiful) toning on surviving pre-1964 coins. Those original mint cellophane packets essentially created a micro-environment that, combined with time, chemistry, and storage conditions, inevitably toned the coins inside to some degree, illustrating perfectly the interplay between packaging and coin chemistry in numismatic history.

Sources: Numismatic conservation studies and expert commentary have documented the above phenomena in detail – for example, coin preservation guides warn of sulfur and acids in old packaging causing silver tarnish (Early Proof Set Packaging Damaged Coins – Numismatic News) (Preservation and Safekeeping of Coins), and historical analyses in Numismatic News and other publications recount the U.S. Mint’s mid-century packaging changes and their effects on coin surfaces (Early Proof Set Packaging Damaged Coins – Numismatic News) (The Evolution of Proof-Set Packaging – Los Angeles Times). Classic numismatic references (e.g. Miller’s Morgan and Peace Dollar Textbook, 1982) explain the thin-film interference chemistry of coin toning (What causes coins to tone – ICCS), while modern experts at PCGS, NGC, and the Canadian Conservation Institute have published guidelines on preventing unwanted tarnish (What causes coins to tone – ICCS) (Caring for your coins – Bank of Canada Museum). The consensus of both scientists and coin collectors is that the pre-1964 mint cellophane wrappers, combined with ambient sulfur, oxygen, humidity, and time, are the driving factors behind the distinctive toning seen on those coins in original packaging. The toning is a product of natural tarnishing processes – sometimes accelerated by packaging materials – that were not fully understood or mitigated by the Mint until packaging technologies improved in later years.

Watch this video for more information

Thanks for visiting!

Leave a Reply